Picture this for second.

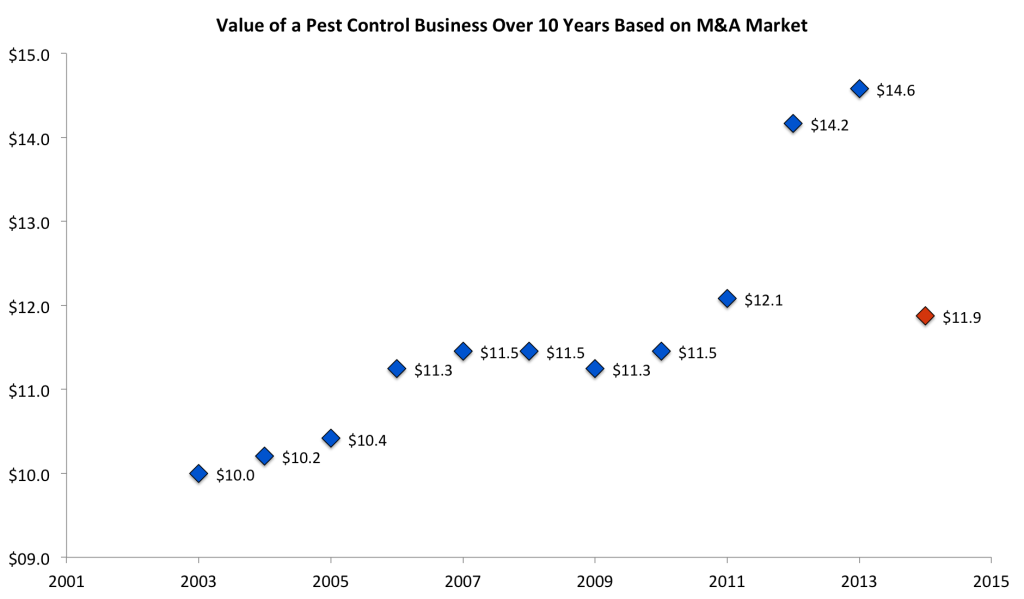

We just jumped into a time machine and went back in time exactly 10 years — it’s now September 15, 2003. We landed at a closing table whereupon an owner was about to sell his pest control business for exactly $10 million. We quickly grabbed the seller and all of the documents from the table (financial statements, operational information, etc.) and brought them back with us into the future, to a closing table, on September 15, 2013. All else being equal, that seller would be receiving a wire transfer for $14.6 million, instead of $10 million.

Let’s not stop there… that’s not the whole story. Upon looking through the information on the seller’s business, we discover that the business was organized as a C corporation.

So in 2003, the seller was faced with double-taxation (upon the sale of assets, a C corporation pays federal and state corporate tax and then the selling shareholders are taxed at personal, long-term capital gains rates).

Unfortunately, since we were just in 2003 ten minutes ago, we still have a C corporation to deal with.

However, unlike for the seller of “September Past,” for the seller of “September Present” it’s a whole new world. Up until late 2012, selling the stock of a C corporation was unheard of in the pest control industry. So the only way not to pay taxes on over 50% of the proceeds from the transaction was to bifurcate corporate and personal goodwill — and only if you could justify it, and many of us cannot.

However, over the last ten months, large, national acquirers have been doing stock deals for premium companies. So on September 15th, 2003, the owner would have walked away with $6 million after paying corporate taxes but before paying personal capital gains taxes. Today, September 15, 2013, we did a stock deal, so walked away with $14.6 million before personal capital gains taxes. Doing a stock deal allowed us to save millions of dollars in taxes.

In ten years, we were able to sell the exact same company for about 150% more money. Further, we are in an environment where the acquirer will actually allow the tax benefits of the deal to go to us, the sellers — something that has never happened before in the US Pest Control Industry. Our proceeds before personal capital gains taxes increased 240%! For a lot of shareholders, that’s the difference between a comfortable retirement and a fantastic retirement.

What’s Going On?

Earlier this year, Anne Nagro, a writer from PCT Magazine interviewed me for the PCT Top 100 List cover story, which included commentary on the current M&A market. Since the purpose of the article was the PCT Top 100 List, not the M&A market, Anne only used a small portion of our interview. So I thought I would begin this article with an excerpt from the transcripts of the PCT interview that you didn’t see, in order to set the stage. It will give you a good idea of where my head was in April of 2013, and then we’ll walk through our current analysis as to where the market is today in September 2013 and why:

Nagro: Will M&A continue at this level in 2013? What’s driving these valuations?

Giannamore: As a business owner, when you open the financial press and the stock market is at an all-time high and central banks are printing almost hundreds of billions of dollars a month in monopoly money, it’s 1999 again and it ain’t gonna last.

For a company that would typically sell for $10M, it’s a $13M company today … and soon, it will once again be a $10M company.

I’ve seen this play out twice already in my career. Business owners don’t realize that the stock they own in their private company fluctuates in a similar, though not exact, manner to the public equity markets and some business owners are about to learn a lesson. Those that sold last year and those who are in process right now in 2013 will sell at the top of the market. The bubble will burst, and unfortunately it is probably going to make 2008 / 2009 barely look like a dress rehearsal.

In regard to our earlier discussion on sale process, business owners need to keep in mind that empirically, those shareholders that sell a pest control business through a competitive, auction process tend to see purchase prices 5% to 25% higher than if they only deal with one buyer. For example, one of our clients engaged us last autumn after he had what he deemed an acceptable offer in hand from a strategic acquirer. After a competitive sale process, the final offer resulted in a purchase price 21% higher than the original offer and the structure of final LOI was dramatically more favorable to him from a tax perspective.

Companies like Western Exterminators that don’t go through full process, tend to leave money on the table and skew statistics. Pest control operators are great at saving a nickel or dime here or there on fuel and chemicals, but when it comes time to sell their largest asset, they are romanced by know-nothing, do-nothing business brokers who are themselves former pest control operators. Or, they just call up Orkin, because they heard ‘Orkin is paying the most’… which is nonsense. They can never know who is paying the most. I can’t know who is paying the most until there is price discovery through a competitive process, and I do this 10 hours a day, every day on five continents. How is it that someone who does this once in his life can know better?

I am certain that M&A will continue like this over the next few months as the acquirers’ cost of capital is extremely low and they have massive cash reserves. I think that we are rapidly approaching a zenith, however, and acquirers will begin to realize that they can’t get the returns they need by paying what they are paying now. We are seeing a secular decline in multiples for smaller and “less special” companies and the market is beginning to peak for the more quality acquisition targets. I am going to bet that over the next six months, the highest acquisition multiples will be history and we will revert back to the long-term mean … that is until this massive, cheap money-induced bubble bursts, and then we’ll all have much bigger problems to worry about than acquisition multiples.

Just like the equity markets, the M&A markets never “crash up,” there is a crescendo, but when the window closes, it typically slams shut.”

Today’s M&A Market

Per the interview above, in April of 2013, I believed that we were rapidly approaching a zenith of in the US pest control M&A market. I now believe we’ve arrived.

In this article, I am going to walk you through the supporting analysis. Like anything you read, you should be skeptical. You should use your own logic and reason to draw inferences and conclusions from the data presented.

Why should you place any credence in this study? As the largest investment bank in the world with a valuation and M&A advisory group dedicated exclusively to the pest control industry, Potomac maintains the largest pest control transaction database of its kind. Because many of our assignments involve advising public companies as well as valuing pest control businesses for the Internal Revenue Service and state and federal courts, we are meticulous about collecting and analyzing data, not only from Potomac transactions and assignments, but also from the acquirers and sellers themselves.

Today we going to rely on information from the US Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis and the Potomac database to review over 300 pest control transactions spanning a period of over 13 years.

How Acquirers Value Acquisition Targets

Before we get into our analysis, we need to spend a few minutes discussing how acquirers value acquisition targets. Keep in mind, the purpose of this article is not valuation so we’ll be brief.

An acquirer begins the valuation process by building detailed cash flow projections on the target company. Based on all relevant quantitative and qualitative factors (i.e., risk, such as management and recurring revenue, resources and capabilities, revenue enhancements, cost savings, etc), the acquirer will discount that stream of cash flow back to the present using a discount rate — or the acquirer’s required rate of return. It’s from this discount rate, that takes into consideration growth rates, risk factors, etc, that we derive the capitalization rate. The capitalization rate is simply the discount rate minus the long-term growth rate. We’re now starting to get deeper into valuation than I wanted to. However, what’s important for you to understand is the capitalization rates are implied from the purchase price and terms paid for acquisitions based upon the above-referenced analysis. Acquirers don’t pull multiples out of thin air because that’s the “going rate.”

In order to filter out the noise and flawed conclusions that come with relying on multiples, our analysis instead relied upon that which actually drives transactions: returns analysis.

We used two valuation statistics:

- Implied internal rates of return

- Capitalization rates

Keep in mind, the goal of this article is not to write a corporate finance text, but rather show you how valuation statistics have changed over time. In order to do that, we used the two main tools that the acquirers themselves use to value acquisition targets instead of using derivations, such as multiples.

In its simplest form, a capitalization rate yields a value by dividing the firm’s net cash flow to invested capital by the capitalization rate. For example, if a firm is generating $500,000 in net cash flow to invested capital and we are employing a 20% capitalization rate, the enterprise value of the firm is $2.5 million ($500,000 divided by 20%). Some of you might look at that and say, “Well, isn’t a capitalization rate just the inverse of a multiple? In the example above, it’s the same thing as saying $500,000 x 5 (or 1/.20)?”

The short answer to that question is yes. The long answer, however, is that it’s a little bit more complicated than that.

The capitalization rates we use for the index are derived from the discount rate, or the acquirers’ required rate of return and is used over a period of five years or longer. So while the capitalization rate gives us a back-of-the-napkin solution, it’s not entirely complete, but is useful for our purposes.

The capitalization rate is calculated by adjusting the discount rate used in discounted cash flow analyses —the primary tool used by Rentokil, Terminix and Orkin to value acquisition targets — by the projected growth rate in net cash flow of the target.

By analyzing over $1 billion in pest control acquisitions over the last thirteen years, Potomac has built a index based on implied capitalization rates — the Potomac Pest Control Group Capitalization Rate Index, or PPCG Cap Rate Index.

In this study, we’ve used the PPCG Cap Rate Index which illustrates prevailing, implied capitalization rates being used by acquirers. It is calculated in a very similar manner to other indexes such as LIBOR — through empirical statistical analysis of actual transactions as well as interviews with corporate development officers and senior executives. This index is used by at least one of the top five global pest control firms in its corporate development and M&A process and Potomac has used it unchallenged for the last seven years in all of our pest control appraisals for shareholders, the IRS and state and federal courts — and we’re the largest appraiser of pest control companies in the world.

What do capitalization rates tell us?

Capitalization rates tend to decrease in low interest rate environments for a variety of reasons that we aren’t going to get into right now. But we’ll tie this all together later in the article, for now, keep in mind that the lower the capitalization rate, the higher the implied value of the firm.

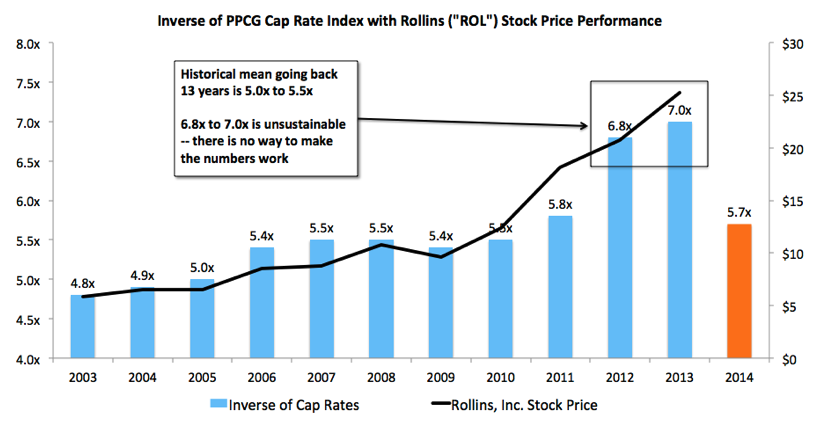

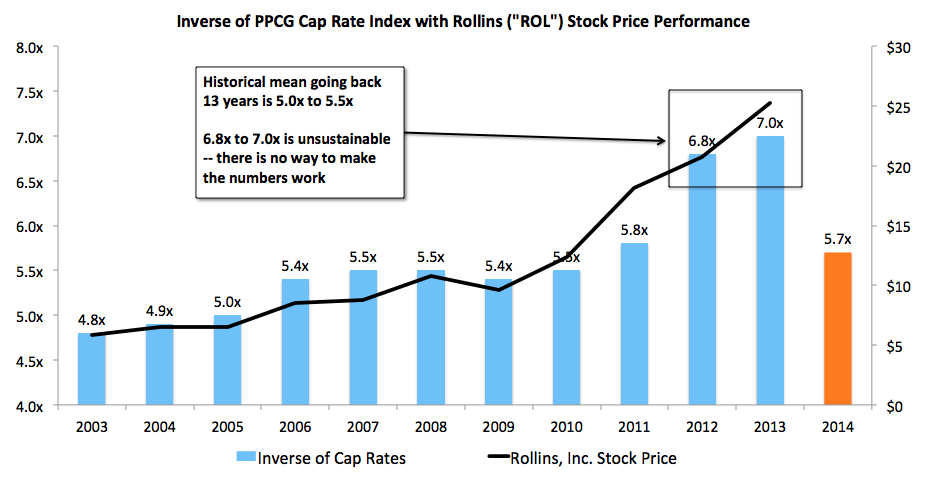

This might be a little fuzzy right now so let’s take a look at the first chart, as they say, a picture is worth a thousand words:

I’d like to draw your attention to the blue columns, which are graphical representations of capitalization rates.

As you can see, as prevailing, long-term interest rates (blue line) declined, so did implied capitalization rates. While we do believe there is a cause-and-effect relationship between long-term interest rates and capitalization rates, that’s not the whole story… stay with me and we’ll get into it.

The black line shows implied internal rates of return (IRRs) for year one (the first full year after an acquisition). Calculating the IRR for an acquisition is the single most important calculation that acquisitions departments make. So for example, when Orkin, Rentokil or Terminix begin to analyze your business in order to make an acquisition, the first thing they are going to do is build a cash flow model that looks at internal rates of return over 1, 3, 5 and 7 years (sometimes even longer).

The dark blue line depicts the long-term interest rate (GS20) published by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

In its simplest terms, the IRR calculates the return on investment projected by an acquisition. In order to determine a purchase price, the acquirer does two things:

- First, it determines what the minimum return it is willing to accept from the acquisition. This is called a hurdle rate and it’s typically between 10% and 18% depending on a variety of factors (i.e. the acquirer’s cost of debt capital, cost of equity capital, the unique attributes of the acquisition target, competition from other acquirers, etc.). Companies like Orkin, Scotts, Rentokil, etc., typically set hurdle rates as part of their business and corporate financial policy and use these hurdle rates for a variety of investments, not just acquisitions. While a company might have a corporate hurdle rate set at 16%, they are often willing to accept returns below the hurdle in the short term in favor of larger, longer-term returns. For example, if I am the director of acquisitions for Orkin and my mandate is a 15% IRR, I might be willing to accept a 10% IRR in year one in order to beat Terminix in a competitive bid to acquire, if I know that I can make it up with revenue enhancements, yielding a 20% return by year three.

- Second, the acquirer backs into a purchase for an acquisition target by asking himself (and his excel spreadsheet): What can I afford to pay for the target today and get a return of 15% (for example, if that’s the hurdle rate) based on the reasonable financial projections I have made.

So by looking at a tremendous number of completed acquisitions, making judgments as to what assumptions the acquirers used to project performance into the future and comparing those assumptions to the terms and aggregate purchase prices paid we are able to impute, or reverse engineer, if you will, internal rates of return considered acceptable by the acquirer at the time of the acquisition.

Why is this important?

It’s extremely important because for the first time in at least the last thirteen years (as far back as we’ve done the study), acquirers have begun to accept returns at or near their weighted average cost of capital (“WACC”), and in some cases, below their WACC.

Let’s take Rollins, the parent company of Orkin, as an example. Rollins has the lowest cost of capital in the industry (around 8%). Theoretically, Orkin needs to get an internal rate of return above 8% on an acquisition, otherwise it is destroying value by doing the deal. But it doesn’t end there, in order to create value, Orkin may need to target a hurdle rate of 15%, for example. If Orkin needs a 15% return, and it has the lowest cost of capital in the industry, other acquirers will need to target a higher hurdle rate, or desired return.

Implied Rates of Return in Unsustainable Territory

In the chart above, the black line shows you that year-one IRRs have remained pretty constant at between 14% and 16% over the years. However, in 2012 accepted returns took a nose dive which has continued into 2013 (illustrated by the black box).

In 2012 and 2013, acquirers have been willing to accept low double-digit and high single-digit rates of return on transactions. This is not sustainable and in many cases, is not creating value for the acquirer. What it’s doing is allowing these large, national companies, such as Rentokil, Orkin and Terminix to deploy capital that would otherwise be sitting on their balance sheets or be returned to shareholders.

So in 2012 and 2013, we believe that acquirers have been willing to pay purchase prices that are so high — the accepted returns are below their corporate hurdle rates — in order to compete on transactions. As I said, this is not sustainable.

The orange bar shows what we believe to be educated guess as to what might happen in 2014, which we’ll get into a little later.

Why Are Acquirers Paying These Prices?

It’s no secret that the US economy is in shambles. With many pest control companies barely growing at the government reported rate of inflation and Obamacare on the horizon, it certainly is not strange to ask: “Why this dramatic run-up in valuations?”

Let’s look at the facts:

- Since the 2008 financial crisis, Western governments have created a tremendous amount of money out of thin air in order to “jump-start the economy.” It’s common sense that additional money chasing the same amount of goods and services, will drive up prices.

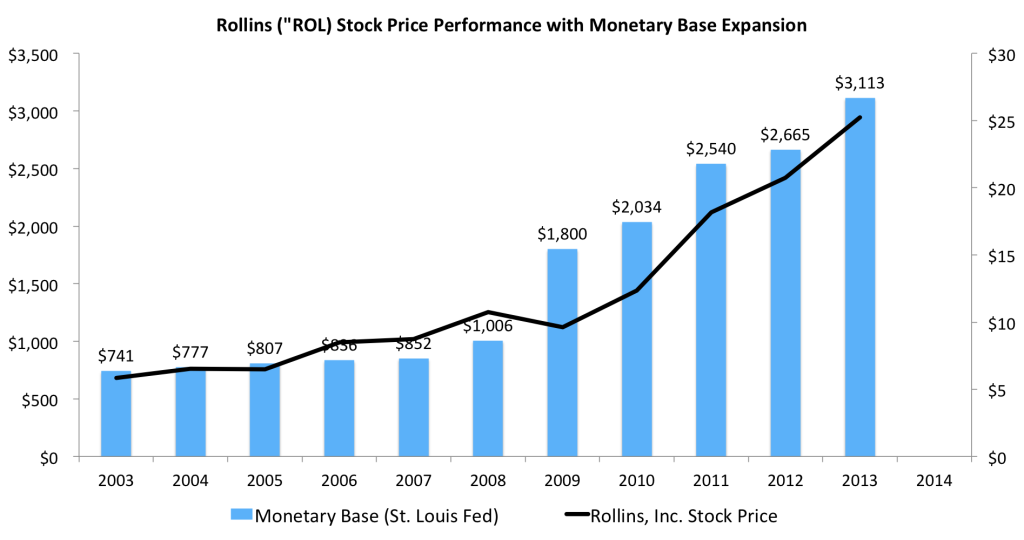

- According to the St. Louis Federal Reserve, the monetary base has increased from $741 billion in 2003 to $3.1 trillion in April of 2013, a whopping 420% increase in the money supply.

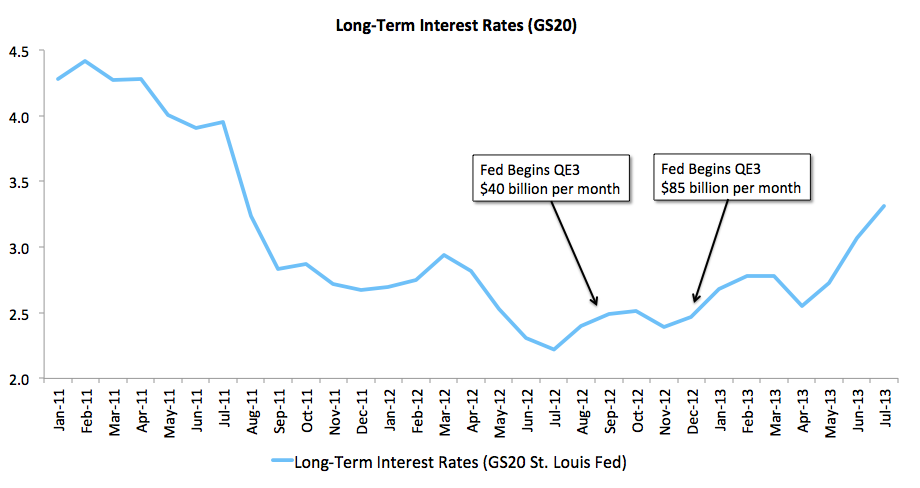

- The Fed has continued to pump $85 billion of newly printed money into the economy per month since December 2012 (they were “only” printing $40 billion from September of 2012).

- By the summer of 2012, long-term interest rates were the lowest they’ve been in my lifetime and most of yours.

When you print trillions of dollars of new money, it has to go somewhere, and where it typically ends up is higher order capital goods, or the means of production. Examples are real estate, commodities and equities.

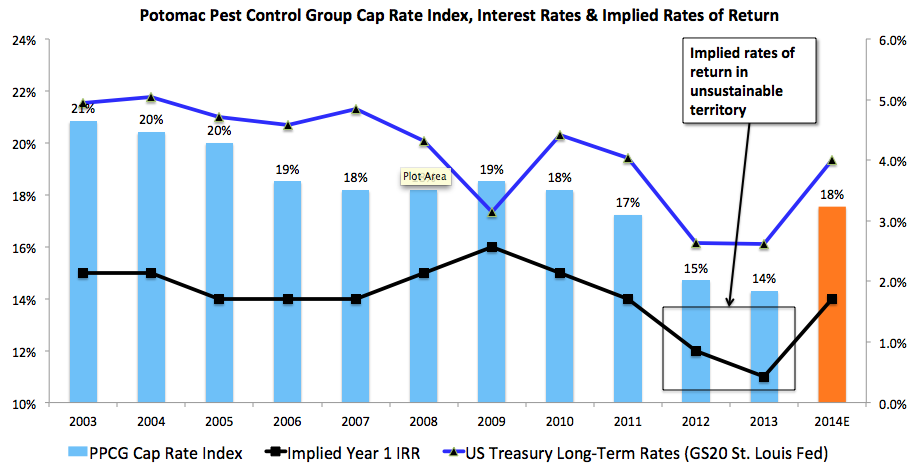

The chart below shows the Wilshire 5000 Total Market Index since 1971. The Wilshire 5000 is an index of all stocks actively traded in the United States.

Per the Wilshire 5000 Index above, you can see that the stock market is in extreme bubble territory. We’ve experienced a dramatic run-up in asset prices over the last few years which is a direct result of the Federal Reserve printing a tremendous amount of money. This creation of new money has artificially depressed long-term interest rates to all time lows.

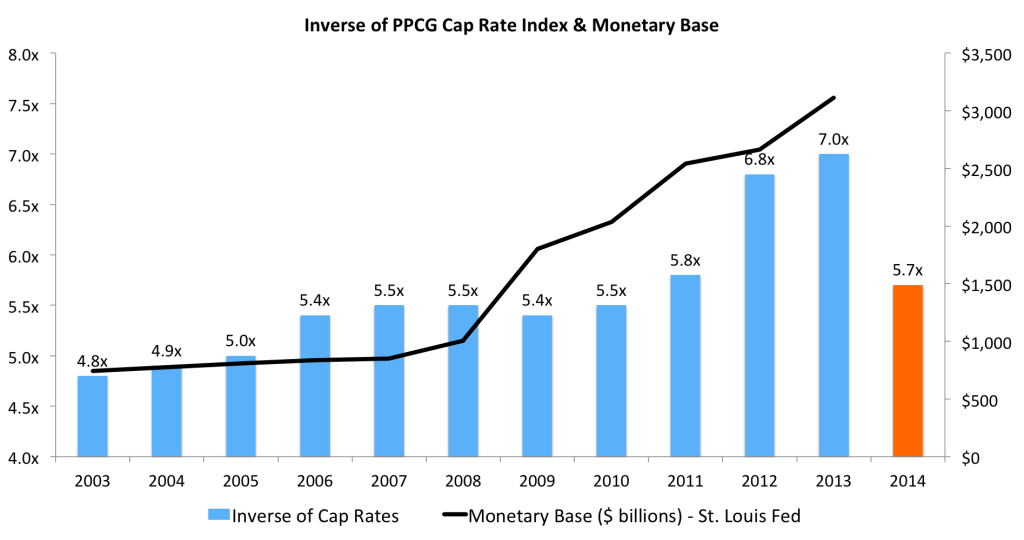

If you have any doubt that the Federal Reserve pumping $85 billion per month of new money into the money supply (“Quantitative Easing 3” or “QE3”) is not having an astounding effect on the value of your business, and asset prices in general, take a look at this.

In the chart above, we’ve inverted the PPCG Cap Rate Index (blue columns) and layered on the increase in the monetary base, which has increased from $741 billion in 2003 to $3.1 trillion as of April 2013 — which as you can see by the black line, largely occurred from 2008 through present. The blue columns, which illustrate the inverse of the capitalization rate can be viewed as Aggregate Purchase Price / Net Cash Flow to Invested Capital. Translation, the higher the multiple, the higher the purchase price. Thus far in 2012 and 2013, we’ve seen some of the highest purchase price multiples in over a decade.

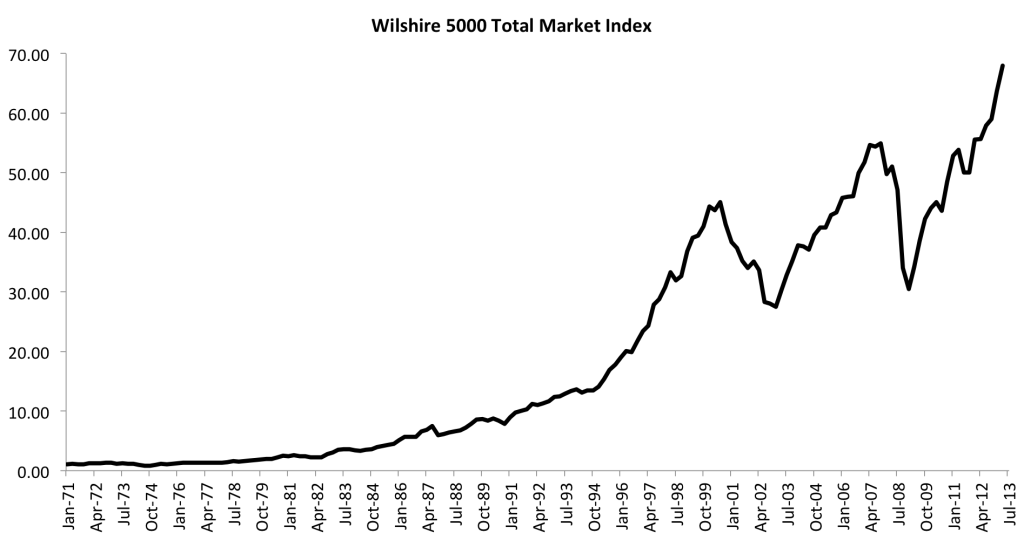

Rollins (“ROL”) as a Barometer for the Industry

In the chart below, we’ve taken the inverted PPCG Cap Rate Index and layered on Rollins’s (the parent of Orkin) stock price performance (the black line).

As you can see, the valuation multiples paid in the pest control industry have tracked closely with Rollins’s stock price performance. Keep in mind, this chart is linear, and not logarithmic — further it doesn’t take into consideration Rollins’s total shareholder return, which includes dividends.

Is there a cause and effect relationship? No.

Because if we continue to peel back the onion, we begin to understand that Rollins’s stock price performance is also a symptom of the greater problem — the tremendous amount of money the Federal Reserve is printing. I believe that if the Federal Reserve weren’t printing billions of dollars in new money per day, Rollins would be trading at $10 per share, instead of $25. So just like the increase in purchase price multiples paid for acquisitions, Rollins stock price increase (in fact, the entire stock market) is a symptom of tremendously expansive monetary policy, or asset price inflation. The chart below illustrates ROL’s stock price performance as the monetary base dramatically expands.

At some point in the very near future, one of two things is going to happen:

- The Fed is going to turn off the cash spigot and valuations will collapse across the board, similar to what we saw back in 2008 / 2009 — but probably on a much grander scale this time; or,

- The Fed will continue to print money (which is the most likely scenario), in order to temporarily avoid the first scenario, which will only serve to kick the can down the road. The big issue here is that the Fed only controls interest rates in the short term, the market controls interest rates in the long-term and we are already seeing a steady increase in rates from their low point of 2.2% in July 2012 to the current rate, as the printing of this article 3.3%. The increase in long-term rates will raise acquirers’ cost of capital and they will look back on 2012 and 2013 and realize that their eyes were bigger than their stomachs and doing deals at projected IRRs of less than 14% to 16% is not sustainable — which will cause the pendulum to swing to the other extreme. Remember, higher IRR hurdle rates mean low purchase prices for acquisitions.

As illustrated in the chart above, long-term interest rates bottomed out in the summer of 2012 and have since increased 150% in just twelve months. As the Fed continues to flirt with tapering QE3, we believe it’s likely that rates will hit the low 4%’s by early 2014 and acquirers will begin to tighten up the returns they are willing to accept, from the high single digits / low double digits back to 14% to 15%, which will cause the capitalization rates on transactions to increase, lowering purchase prices as we revert back to the historical mean.

Back to the Time Machine

In the beginning of the article we discussed the seller going to the closing table in September of 2003. We were were curious as to what would happen if we applied capitalization rates, implied rates of return, and derivative multiples to his business each year for the last ten years.

So, we went back to our massive database and constructed a timeline, applying prevailing acquisition statistics to our seller of “September Past’s” business each and every year for the last ten years. Keep in mind, we are applying the statistics each year de novo, as if he were at the closing table on September 15th of each year with the exact same business. The chart below illustrates the imputed, aggregate purchase price of his business as a result of a fully-vetted, competitive sale process. Further, we added the blue line which includes the monetary base statistics from the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank.

The dollar amount indicated by each marker shows what would have been wired into the seller’s bank account that day. By the end of 2014 and into 2015, we believe the market will begin to revert back to its historical mean and eventually the purchase price will settle somewhere between $10 and $12 million.

While the typical business broker out there will spew off, year after year, the same nonsensical revenue multiples to business owners who might be interested in understanding what their business are worth. The reality is, the market is dynamic, ever-changing, and as you can see by the chart above, just about every year would have yielded a different purchase price for the identical asset.

So What’s an Owner to Do?

While I do think that acquisition multiples have hit a zenith in the industry, there is a big question as to how long that will last. Three months? Six months? Another year? Because the economy is no longer driven by fundamentals, but rather by central bankers manipulating the prices of assets, you can rest assured that the Federal Reserve will do everything in its power to continue to prop up an otherwise moribund market.

Although the Fed continues to recklessly print new money, the market is on the verge of disciplining irresponsible governments and central banks for this shenanigans. We can see this when we look at what is happening to long-term interest rates. Quantitative easing over the last few years has dramatically pushed down long-term interest rates, however, it’s no longer working as before.

When the day comes that the Fed pulls the plug, assets prices will crater — that’s a guarantee proven out by centuries of history. Take, for example, on June 19th, 2013, when Ben Bernanke hinted that the Fed would announce a tapering of money printing at the September 2013 policy meeting and the stock markets lost over 4% of their value over the subsequent three trading days.

When you listen to a lot of the business brokers running around the pest control industry, just about every year is the best time to sell. For them, the sky is always falling and it’s a perfect storm to do a deal. Since Potomac is in the business of advising shareholders on the sale of their companies, this article might look a little self-serving. It’s not. For those of you who know me personally, you know that I never suggest that now is the time to pull the trigger, because no one can predict the future.

At last year’s PCT Virtual M&A conference a few of my co-presenting business brokers suggested that “now” was the best time to sell. And of course last August was the best time to sell up until last August. However, right now is a better time to sell than last August, so in retrospect, last August was a bad time to sell.

As business owners you shouldn’t be in the business of trying to time the market. Even if you were to sell your business today, at the zenith of the market, if don’t have a sophisticated advisor running a competitive sell-side process, you won’t be selling at these sky-high multiples. Western Exterminators most likely left money on the table as well as a lot of other sellers because they negotiate with only one acquirer. Or worse, they hire a business broker who convinces them that pest control companies sell for 1.0x sales and puts a one-size-fits-all asking price on the business.

Over the course of the last 12 months alone, I have seen purchase price offers move up millions of dollars from the first offer to final LOI through formal, sell-side processes. While the external environment has a large impact on what your business is worth, going through the appropriate process, in my opinion, can have an equally large impact on the final purchase price.

For those of you who intend to sell soon, now is a great time. But I can’t assure you that four months from now won’t be better. Based on the all of the above, one thing is certain, this current environment is not sustainable.

I’ll leave you with a final thought. One of the biggest mistakes that sellers make is that they believe their business has only one value. The reality is, a business has a range of values depending on who is valuing it. Even though I do this every day of the week, it’s almost impossible for me to call which acquirer will pay the most at the onset of a sell-side process. It’s only by causing acquirer to act under intense time pressure to competitive bid for an asset to we get “price discovery” and truly extract the highest price that the market will bear. If you are ever faced with negotiating on your own behalf with one acquirer, remember the words of mentor Dennis Roberts:

“I have always considered the seller facing off against a lone prospective buyer to be almost as inconsequential in the process as a chicken flapping its wings, facing off against a great white shark. The buyer, just like the great white, is in heaven – and so, too, will the chicken be . . . shortly.”