1. Introduction

An overview of the tax ramifications of the sale of a C corporation’s assets and how the sale of personal goodwill as an asset class can offer a seller substantial tax savings

Over the next few years, a considerable number of pest control operators will exit their businesses and retire. Many long-established pest control companies are organized as C corporations, which creates serious tax issues for both buyers and sellers. If you own a pest control company organized as a C corporation (or an S corporation subject to built-in gains)[1], you are likely staring down the barrel of a nasty tax cannon that can eat up more than 50% of the sale proceeds due to oppressive double taxation. This article explores innovative techniques that pest control operators are currently utilizing to mitigate the tax bite of selling a C corporation. Although this topic is of paramount importance to sellers, buyers are well advised to understand the strategies and techniques discussed in this article as last minute tax surprises can stop a deal dead in its tracks. Buyers who arm themselves with this knowledge might be able to avoid a deal dying at the closing table due to double taxation surprises.

This article discusses the innovative approach of bifurcating goodwill into both corporate and personal components in the context of an asset sale by a C corporation. I was compelled to write this article due to the glaring void of information available in the industry in regard to how this very powerful strategy can drastically reduce tax liability at the time of sale. In our practice at Potomac, we’ve encountered a disheartening number of pest control operators who have realized too late the tax-savings potential of bifurcating goodwill. Although this is a very technical topic, I’ve attempted to make it accessible to both the practitioner and layman. In doing so, I have purposefully focused on the identification and conveyance, rather than the valuation of personal goodwill – a technical topic best left to your qualified advisors. Finally, this article is not intended to render tax advice, but simply provide a high level overview of selling personal goodwill in the pest control industry. Always seek professional advice when contemplating the purchase or sale of corporate assets.

The Sale of a C Corporation and Double Taxation

Double taxation arises from the sale of corporate assets, whereby the corporation is taxed on its gains at ordinary income tax rates and the shareholders are taxed on the distribution at long-term capital gains tax rates. This is a particularly common occurrence in the pest control industry as acquirers are overwhelmingly reluctant to acquire the stock of a closely held company and prefer instead to structure the acquisition as an asset purchase for the following reasons:

- In an asset sale, unlike a stock sale, the buyer receives a tax basis in the acquired assets equal to the purchase price of those assets (i.e., a “step-up” in basis). Naturally the buyer’s objective is to pay as low a price as possible for the target, and by getting a step-up in basis, the buyer is generally able to deduct and write off the acquisition costs quicker. The tax benefits to the buyer in a pest control acquisition are typically substantially more favorable under an asset purchase than a stock purchase.

- Acquirers need to be very careful when they acquire a pest control company due to EPA issues, ERISA claims, NLRA offenses, damage claims or any other liability, disclosed or undisclosed, that might not have been addressed in diligence. By acquiring assets, buyers can pick and choose which of the target’s liabilities they will accept. Buying assets, as opposed to stock, while not always entirely effective against previous claims and undisclosed liabilities, will put the acquirer in a considerably better position if ever confronted by a claimant.

…many pest control companies have corporate policies against doing stock deals, period.

For these reasons, it is extremely rare to encounter a pest control transaction that is consummated as stock purchase. In fact, many pest control companies have corporate policies against doing stock deals, period. For those of you who own a flow-through entity,[2] the choice of deal structure (i.e., stock purchase vs. asset purchase) will not be nearly as important as the allocation of purchase price. However, those of you who own a C corporation, or an S corporation subject to built-in gains (i.e., within the 10-year conversion window), will most likely be in for an insufferable tax bill upon the sale.

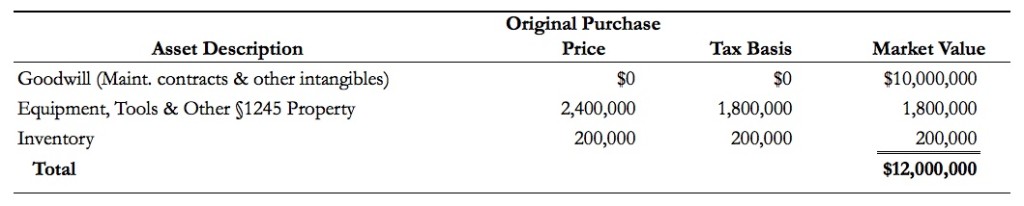

Without careful tax planning, the sale of C corporation generally results in a punitive amount of taxation – double taxation that is. Before we examine how to mitigate taxes, let’s take a look at the example of Excel Environmental, Inc.[3] (“Excel” or the “Company”), in order to understand the tax ramifications of a typical asset sale. Assume the sole shareholder of Excel, Mr. Brown, just received a letter of intent (LOI) from an acquirer that desires to purchase substantially all of the assets of the business. The LOIcontemplates a purchase price allocation as follows:

If Excel Environmental is organized as a single member LLC (or any other flow-through entity), its assets are sold for $12 million in cash, and the purchase price is allocated according to the market values shown above in Figure 1.1. As the sole owner of a flow-through entity, Mr. Brown will recognize $10 million of long-term capital gain on the intangible value of the business attributed to the pest control contracts and associated intangible assets. In the current tax environment, assuming a combined state and federal long-term capital gains tax rate of 20% (15% federal and 5% state), Mr. Brown would pay $2 million in taxes upon the sale ($10 million x 20%) and receive $10 million in after-tax proceeds ($12 million in proceeds minus taxes of $2 million) from the sale of his business. Because the purchase price is allocated according to the fair market value of the tangible assets ($1.8 million in equipment and $200,000 in inventory), which also happens to be equal to the Company’s tax basis in those assets, only the sale of goodwill is taxed.

Now let’s assume that Mr. Brown, like many of you, started this business decades ago before flow-through entities were in vogue and the company is organized as a C corporation. Assuming a combined state and federal corporate income tax rate of 40%[4], upon the sale of assets, the corporation would pay $4 million in income taxes ($10 million x 40%). Upon the liquidation of the corporation and distribution of the proceeds, Mr. Brown would then be required to pay long-term capital gains tax on his capital gain. Assuming a basis of $500,000 in his stock, and a combined state and federal long-term capital gains tax rate of 20%[5], Mr. Brown’s personal tax bill would be $1.1 million ($5.5 million x 20%). After paying this second level of tax, Mr. Brown would receive a total of $6.9 million from the sale of his business.

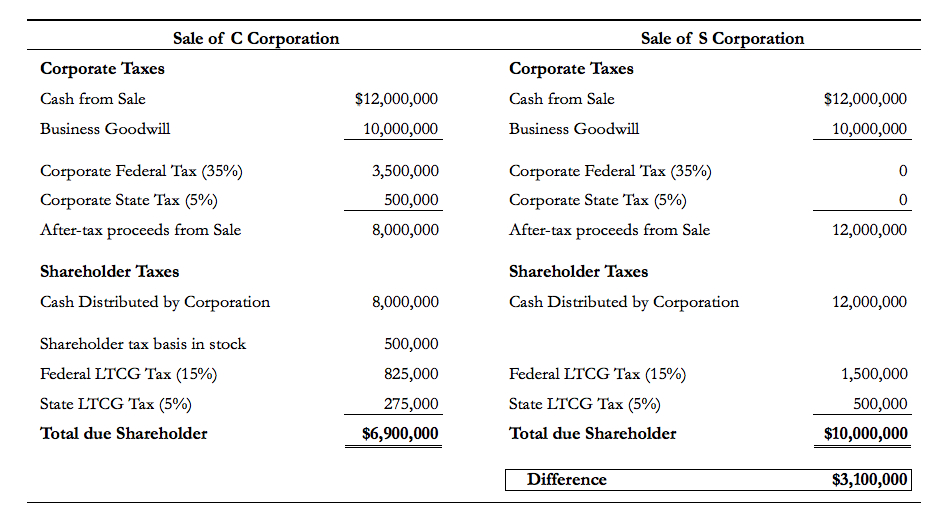

Both transactions would have identical tax consequences to the buyer; however, the net, after-tax proceeds to Mr. Brown, the seller, are dramatically different: $10 million versus $6.9 million. In this particular case, Mr. Brown ended up paying an additional $3.1 million in taxes simply because his business was owned by a C corporation instead of a flow-through entity. The preceding calculations are illustrated in the figure below:

The Zero-Sum Game

If the transaction above (Excel as a C corporation) had been structured as a stock purchase, as opposed to an asset purchase, the tax ramifications would have been very different for Mr. Brown. His tax liability would have been much closer to the lower amount he paid in the example of Excel as an S corporation. Under a stock sale scenario, Excel would not have sold any assets, rather Mr. Brown, the shareholder, would have sold his stock directly to the acquirer. Under a stock sale, the Company would have no tax liability because it did not sell anything, and Mr. Brown would only have paid taxes on the capital gain in his shares of stock (the amount above and beyond his tax basis in the stock). So why not just structure the deal as a stock purchase instead of an asset purchase?

Certainly the seller can insist on a stock deal, and most do. However, there are very real tax consequences for the buyer in structuring the transaction as a stock purchase, not to mention the legal issues surrounding undisclosed liabilities that we discussed earlier. If an acquirer were to purchase the stock of Excel (the C corporation) from Mr. Brown, it would also acquire the Company’s tax basis in the assets owned by the corporation. Unlike under an asset purchase, the buyer would not be able to step-up its basis to the purchase price of the assets acquired, which would result in a dramatically less favorable deal for the buyer. This is a zero-sum game and what is good for one side of the deal is generally bad for the other from a tax perspective. For example, Excel’s tax basis in its assets is $2 million and as a stock purchase, the acquirer would be purchasing this $2 million basis on a $12 million deal, whereas by purchasing the assets of the Company, the acquirer could step-up its basis to $12 million. The $10 million increase in tax basis allows the acquirer to amortize and deduct the costs of the acquisition over 15 years, or more than a half million dollars per year, which equates to millions of dollars in economic benefit (tax savings) foregone by the buyer.[6] With this in mind, no buyer would acquire the stock of a pest control company unless it absolutely had to, and there are rarely, if ever, any situations whereby an acquirer absolutely has to do anything.

Goodwill Holds the Key

If you own a C corporation, you’re not necessarily destined to Mr. Brown’s fate of double taxation, although most of you will end up there because you will not seek proper tax advice and instead rely on your accountant, who most likely has never considered what we are about to discuss.

For any pest control company of value, the largest asset transferred in a sale is intangible in nature and referred to as “goodwill.” The Internal Revenue Service defines goodwill as “the value of a trade or business based on expected continued customer patronage due to its name, reputation, or any other factor.”[7] In essence, goodwill is the value of a business above and beyond the market value of its tangible assets, which equates to the majority of the value of a pest control company. [8]

If you look at any pest control company, you will quickly realize that the majority of its value is not in its fixed or tangible assets, but in its intangible assets. You might own a pest control company that generates $5 million in sales and $1 million in cash flow; however, the company only owns $700,000 in tangible assets. Certainly a business of this size and level of profitability is worth more than $700,000, is it not? The difference between the purchase price and the market value of the tangible assets is the market value of the goodwill.[9]

In the example of Excel Environmental, the Company was purchased for $12 million but only $2 million of the transaction value was attributed to tangible assets, while $10 million was attributed to intangible assets, in this case, goodwill. As we have discussed, when a C corporation sells goodwill, it pays taxes at the corporate level and then the shareholders pay capital gains taxes when the proceeds are distributed to them. What would happen, however, if the company did not really own that goodwill to begin with? What if it is in fact the owner’s “name or reputation” that was responsible for “expected continued customer patronage” and not the Company’s? Could you argue that it is not the corporation that is selling the goodwill, but rather the individual owner, and therefore the company should not be liable for income taxes on the sale of the asset? Absolutely. That argument is made to great success in the pest control industry all the time. If you and your advisors understand how to identify, value and properly bifurcate personal and corporate goodwill upon the sale of your C corporation, you might be in a position to significantly reduce your tax bill. Before we get into the bifurcation process, let’s first get a better sense of exactly what goodwill is.

Types of Goodwill

Thus far, we have discussed what is largely referred to as “business goodwill” or “enterprise goodwill.” Goodwill is easily identifiable in large, well-known companies such as Orkin, for example. When someone hires Orkin to protect his home from pests, he is not hiring the Orkin Man, an individual per se; rather he is hiring a large company that has established mindshare and reputation over the years. However, when someone hires Robert Crandall Exterminating, he may be hiring the company because of Mr. Crandall himself and his reputation in the local market. If Mr. Crandall were to retire, Robert Crandall Exterminating might lose customers, and therefore value, which indicates that Mr. Crandall might own the goodwill personally, and not the company. It is identifying, valuing, and transferring goodwill owned by the shareholder, known as personal goodwill, versus the goodwill owned by the business, or business goodwill, which is the key to mitigating taxes upon the sale of corporate assets.

Personal goodwill has been traditionally associated with professional practices such as dentists, doctors, accountants, attorneys, etc.[10] In this context, it is referred to as “professional goodwill” and is associated with the advanced education, specialized skills and reputation of the owners as opposed to the name and reputation of the organization itself. The courts have routinely recognized the existence of professional goodwill, a subset of personal goodwill, in cases involving marital dissolution. While the courts have recognized the concept of professional goodwill for decades, it has been only recently that a business owner successfully argued in Tax Court the existence of personal goodwill in a non-professional setting. I argue that both professionals and non-professionals can and do give their business values. Pest control operators that maintain personal contact with their customers and suppliers, and have developed novel methods for assisting their customers in controlling their pest problems can give their businesses significant value and the courts recognize this.

Tax Benefits of Personal Goodwill as an Asset Class

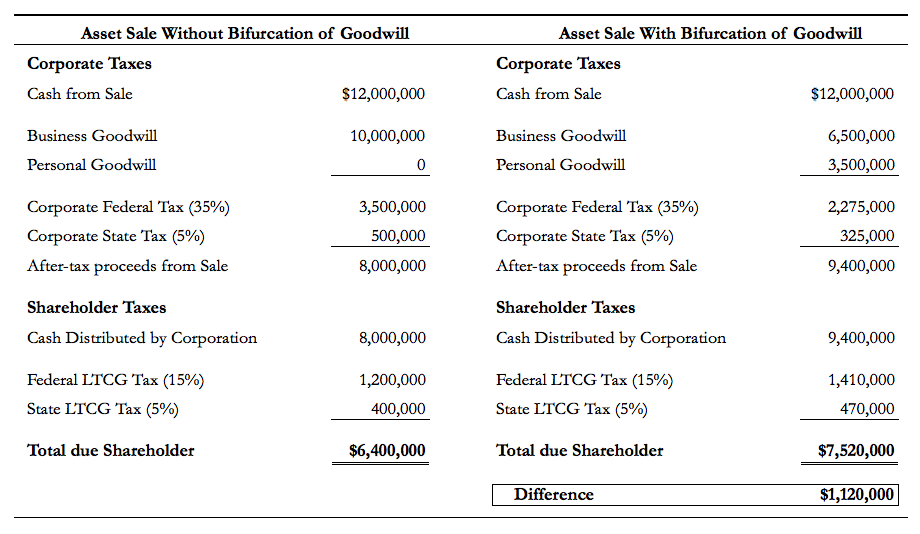

Bifurcating goodwill into that which is owned by the business (business goodwill) and that which is owned by the shareholder (personal goodwill) can have a dramatic impact on the tax ramifications of a corporate sale. Let’s take a look back at Mr. Brown and the sale of assets by Excel Environmental as a C corporation. In Figure 1.3 below, you’ll see the sale of Excel’s corporate assets on the left side, along with the sale of both corporate assets and Mr. Brown’s personal goodwill on the right. By allocating $3.5 million of the $12 million purchase price to personal goodwill, the seller, Mr. Brown realized a total tax savings of 20%, or $1.12 million. Excel is a relatively large, privately owned pest control company, and therefore it is more difficult to argue that Mr. Brown owns a substantial portion of the goodwill personally. However, for smaller pest control companies (generally doing $5 million or less in sales) that are more reliant on the shareholder / operator, this argument might be more supportable and therefore yield greater tax savings for the selling shareholder as a percentage of the total transaction value. This is ultimately a judgment call for the experienced and qualified appraiser in determining the allocation of purchase price.

In the following sections, we will:

- Section Two – Review and analyze important tax court cases that provide valuable insight into identifying and transferring personal goodwill in the context of M&A

- Section Three – Apply what we’ve learned from the tax court cases to effectively transfer and preserve personal goodwill

- Section Four – Discuss the finer points of deal structure and preserving personal goodwill

Although sections three and four draw significantly on what we learn from the case law analysis, Section Two is geared more to the practitioner than the layman (i.e., it’s quite boring), so it might make sense for the casual reader to skip ahead to Section Three and use Section Two as a reference.

2. When Does Personal Goodwill Exist? An Analysis of Case Law

A summary of selected court cases providing guidance on the identification and conveyance of personal goodwill in the context of a corporate asset sale

Although the use of personal goodwill for tax mitigation upon the sale of corporate assets is a relatively new concept, the courts have long-recognized personal goodwill in the context of marital dissolution. In many states, personal goodwill is not considered a marital asset, and is therefore a fiercely disputed topic in divorce court, which has resulted in a body of case law to assist us in our efforts in identifying personal goodwill. In this section, we are going to review some selected court decisions that have served to establish a body of case law surrounding the identification of personal versus corporate goodwill. Later, we will apply this guidance in our assessment of a pest control company. As this is not an exhaustive study, we will rely primarily on cases that deal with personal goodwill in the context of a business sale. Anyone who intends on taking advantage of bifurcating goodwill will be best served by hiring an appraiser who has a strong background in both the following case law as well as the decisions surrounding personal goodwill in the context of marital dissolutions, as the treatment of goodwill in the sale of a business is often similar.

a. Martin Ice Cream v. Commissioner (1998)

While the concept of personal goodwill had been around for decades, it wasn’t until the late 1990s that bifurcation of goodwill gained notoriety as an effective tax avoidance mechanism. In a US Tax Court case, Martin Ice Cream Co v. Commissioner, 110 T.C. 189 (1998), the Court concluded: “This court has long recognized that the personal relationships of a shareholder / employee are not corporate assets when the employee has no employment contract with the corporation. Those personal assets are entirely distinct from the intangible corporate asset of goodwill.” It is with this opinion that the tax court opened the door for the business owner to rightfully separate goodwill that is owned by the business versus that which is owned by the shareholder.

As the story goes, Martin Ice Cream (“MIC”) was incorporated in 1971 as a wholesale ice cream distributor. Although Martin Strassberg founded the company, his father Arnold Strassberg, after a long career in the ice cream distribution business, eventually became a shareholder in the business. It was Arnold’s relationships that had been developed over a 25-year period that were a major factor in the MIC’s success. Arnold developed innovative packaging for ice cream that won him favor with supermarkets and ice cream makers alike. As a result, the founder of Häagen-Dazs ice cream, Ruben Mattus, approached Arnold in 1974 and asked him “to use his ice cream marketing expertise and relationships with supermarket owners and managers to introduce Häagen-Dazs ice cream products.”

Over the years, Martin and Arnold disagreed as to the strategic direction of the business. Arnold wanted to continue to focus on large supermarkets, whereas Martin was more inclined to service small grocery stores. The two partners made the decision to split the business, and Strassberg Ice Cream Distributors (“SIC”) was born. SIC was entirely related to Arnold’s side of the business that catered to the large supermarkets and became a subsidiary of MIC.

In the mid-1980s Häagen-Dazs approached Arnold intent to buy his business, SIC, which at that point had split off from MIC leaving Arnold as the sole shareholder. The assets of SIC were subsequently sold to Häagen-Dazs and the IRS dragged the Strassbergs into tax court. The underlying issue in Martin Ice Cream involved the tax treatment of the 1988 split-off of Arnold Strassberg’s portion of the business, SIC – which was sold to Haagen-Dazs – from MIC. The IRS argued that it was in fact MIC that sold corporate assets (and thereby business goodwill) to Haagen-Dazs and therefore there should be two layers of taxation (corporate and personal) on the sale of those assets. The court disagreed and held: “The benefits of the personal relationships developed by Arnold Strassberg with the supermarket chains and Arnold’s oral agreement with the founder of Häagen-Dazs were not assets of MIC that were transferred by MIC to SIC and thereafter sold by SIC to Häagen-Dazs; Arnold Strassberg was the owner and seller of those assets.”

Although this case does not provide specific guidance on the valuation of personal goodwill, it does provide us some insight as to how the court identified personal goodwill separate from business goodwill in this particular situation. A key component of the court’s finding was that Arnold never entered in a non-compete or employment agreement with SIC or MIC and therefore never conveyed his ownership in the relationships or expertise to either business entity, and therefore they remained his personal assets.

Martin Ice Cream – Key Points

Martin Ice Cream is largely credited with opening the door for the argument that personal goodwill is a saleable asset. Central to the court’s holding was that Arnold had never entered into an employment agreement or non-compete with MIC or SIC, and therefore never transferred ownership in his relationships, knowledge and expertise to the company. In absence of such agreements, Arnold retained the ownership of this goodwill personally and therefore it was his and only his to sell.

b. Norwalk v Commissioner (1998)

In Norwalk v. Commissioner, the tax court recognized a shareholder’s personal goodwill in the context of a corporate liquidation of an accounting practice. In 1985, William Norwalk and Robert DeMarta founded DeMarta & Norwalk, CPA’s, Inc., and were the corporation’s sole shareholders. Both DeMarta and Norwalk entered into employment agreements with the corporation that included covenants not to compete. After seven years of working together, DeMarta and Norwalk decided to cease operations due to the fact that the businesses was not profitable. The two shareholders voted to close the corporation, liquidate assets and distribute them to the shareholders.

“[the] client base, client records and workpapers, and goodwill belonged to them [the owners] and not the corporation.”

Norwalk and DeMarta ended up in tax court because the IRS maintained that the corporation had realized a gain upon liquidation of its goodwill, and that Norwalk and DeMarta each realized a capital gain from the distribution of goodwill from the firm to the individual shareholders. Norwalk and DeMarta argued that “the corporation’s client base, client records and workpapers, and goodwill (including going-concern value)” belonged to them and not the corporation. The court agreed with the taxpayers and stated that it was “reasonable to assume that the personal ability, personality, and reputation of the individual accountants are what the clients sought.” Citing Martin Ice Cream, the court rejected the IRS’s argument stating: “We have held that there is no salable goodwill where, as here, the business of a corporation is dependent upon its key employees, unless they enter into a covenant not to compete with the corporation or other agreement whereby their personal relationships with clients become property of the corporation.” Although both shareholders had entered into employment agreements and covenants not to compete with the company, these agreements had terminated prior to the liquidation of the corporation and therefore did not encumber the shareholders’ ownership of personal goodwill. Based upon the decisions in Martin Ice Cream and Norwalk, one could argue that an employment agreement / non-competition agreement does not permanently transfer ownership of personal goodwill to the corporation, rather that goodwill is “on loan” while the agreements are in effect, with ownership reverting back to the shareholders once the agreements expire.

Norwalk – Key Points

In Norwalk, the court focused on three main findings of fact in its support of the shareholders:

Once the employment agreements between the shareholders and the Company had terminated, the shareholders had no reason to continue their relationship with the company.

- The court reasoned that if the shareholders left the corporation, so would their clients. This fact strongly supports the argument that it was the shareholders who owned the goodwill, not the corporation.

- The court determined that the corporation would have no value independent of the accountants themselves.

Following the Martin Ice Cream and Norwalk decisions, taxpayers have taken somewhat creative approaches to bifurcating corporate and personal goodwill for tax purposes. Specifically, from 2008 through 2010, a few cases, such as Solomon v. Commissioner(2008), Muskat v. United States (2009), and Howard v. Unites States (2010), provide us further guidance on the identification of personal goodwill.

c. Solomon v. Commissioner (2008)

In Solomon v. Commissioner, Robert Solomon and Richard Solomon sold a division of their company, Solomon Colors, Inc., to Prince Manufacturing, Inc. The Solomons had reported to the IRS that they each sold a “customer list / goodwill” directly to Prince, the IRS disagreed. The disagreement between the Solomons and the Internal Revenue Service resulted in a $600,000 tax deficiency for the shareholders and Solomon Colors.

The court acknowledged in its opinion that the “Petitioners [the Solomons] rely on Martin Ice Cream, to support their assertion that Robert Solomon and Richard Solomon sold their personal goodwill to Prince as part of the agreement.” The court went on to explain that this particular case is distinguishable from Martin Ice Cream in three important ways:

- The type of business: “the record does not persuade us… that the value of Solomon Colors in the market was attributable to the quality of service and customer relationships developed by Robert Solomon or Richard Solomon… as a business of processing, manufacturing, and sale, rather than one of personal services, did not depend entirely on the goodwill of its employees for its success.”

- The Solomons were not identified as sellers of any assets in the purchase agreement: “unlike…in Martin Ice Cream…Robert Solomon and Richard Solomon were not named as the sellers of any asset but were included in the sale in their individual capacities solely to guarantee that they would not compete with Prince.”

- A non-competition agreement was not enough: “Prince required non-competition agreements, but not employment or consulting agreements, of Robert and Richard Solomon makes it unlikely that Prince was purchasing the personal goodwill of these individuals.”

The court held that the money “petitioners allocated to Robert Solomon’s and Richard Solomon’s sale of a customer list is actually attributable to their covenants not to compete.” A slightly better outcome than that of the company owning the goodwill, but not exactly the tax consequence the sellers were looking for.[11]

Finally, in Solomon, the court said that although the acquirer required a non-compete from the selling shareholders, it did require employment or consulting agreements, which “makes it unlikely that Prince was purchasing the personal goodwill of these individuals.”

Solomon – Key Points

In Solomon, the court commented that personal services businesses are much more likely to rely on the “goodwill of employees for success” than manufacturing businesses, for example. Pest control companies fit nicely within the service business sector, especially the smaller ones whereby the shareholders have substantial direct communication with customers and suppliers.

As we will discuss in more detail in Sections Three and Four, the court paid close attention to the purchase agreement and noticed that the Solomons were not even party to the agreement. It is very important to make sure that you have a paper trail beginning at or before the Letter of Intent and taken all the way through the definitive purchase agreement and ancillary agreements that explicit name the sellers of the personal goodwill.

c. Muskat v. United States (2009)

In Muskat v. United States, Irwin Muskat filed for a tax refund attempting to reallocate a portion of the purchase price for the sale of his meat processing business to personal goodwill from a covenant not to compete. This case proves to be an interesting read, partly because Muskat uses every argument in the book to battle the IRS, and partly due to the pithy rhetoric of the court.

Muskat sold his family business Jac Pac Foods, Ltd. (“Jac Pac”), to a division of Corporate Brand Foods America, Inc. (“CBFA”). At the time, Muskat owned 37% of Jac Pac’s outstanding stock and was the lead negotiator on the transaction. Following lengthy negotiations, the parties entered into an asset purchase agreement for the sale of Jac Pac’s assets. Muskat agreed that he would continue to run the business after the acquisition, in consideration for incremental payments under both an employment agreement and non-competition agreement. Under the terms of the non-competition agreement, Muskat was to receive $3,955,599 over a thirteen-year period with a $1 million payment due immediately at the closing. After allocating this amount to the non-competition agreement (ordinary income) as opposed to personal goodwill (capital gain), Muskat filed for a refund in an attempt to reallocate the purchase price. The court spent more time discussing how Muskat was not able to overcome the “strong proof” rule than it did on what constituted personal goodwill.[12] However, the court did provide us with guidance on the importance of establishing the existence of personal goodwill from the onset of negotiations and clearly documenting it throughout the negotiating and contracting process. The court had this to say in regard to the reallocation of noncompetition consideration to that of personal goodwill:

In this case, the trial testimony revealed no discussion of Muskat’s personal goodwill during the negotiations. By the same token, none of the transaction documents (including the early drafts of those documents) mentioned Muskat’s personal goodwill. Muskat had ample opportunity to introduce the concept of personal goodwill into the noncompetition agreement (which went through at least five iterations), but he did not do so. And although there is a reference to goodwill in the preamble to the noncompetition agreement, that reference is to an avowed purpose to protect Jac Pac’s goodwill…

…This is telling evidence. In our judgment, the absence of any reference to Muskat’s separate goodwill, combined with this express reference to Jac Pac’s goodwill, makes it extremely unlikely that the contracting parties intended the payments limned in the noncompetition agreement to serve as de facto compensation for Muskat’s personal goodwill.

Muskat – Key Points

The Muskat case further emphasizes the point that it is very important that all transaction documents clearly and explicitly describe what personal goodwill is being sold and by whom (this includes non-competition and employment agreements).

c. Howard v. United States (2010)

The US District Court for the Eastern District of Washington recently provided us further guidance on the bifurcation of personal and corporate goodwill. This case involves a dentist, Dr. Howard, who practiced through a professional corporation. Dr. Howard had written an employment agreement with a covenant not to compete, providing that as long as he was a shareholder of the company and for a period of three years thereafter, he would not compete with the corporation.

In 2002, Dr. Howard sold his practice (personal goodwill) to Dr. Brian Finn and the stock of his professional corporation to Brian K. Finn, D.D.S., P.S. (“Finn Corporation”). Similar to what would take place in the pest control industry, Dr. Finn was interested in acquiring the assets of the business instead of the stock so that he would be able to get a step up in basis on the acquired assets and amortize the purchase price. For Dr. Howard, this would result in double-taxation, so upon the sale, the purchase agreement allocated $549,000 to personal goodwill and $16,000 to a covenant not to compete with Finn Corporation. Later that year the IRS conducted an audit on the sale and charged Dr. Howard with a tax deficiency of $60,129 and interest of $14,792 – the difference between long-term capital gains tax rates and ordinary income rates.

Dr. Howard paid the amount in full to the IRS and then filed a claim for a refund. After six months had passed from the filing of the claim, Dr. Howard filed the lawsuit in order to compel to IRS to issue his refund. Dr. Howard argued that the goodwill that was sold was personal to him, and that he was entitled to claim the proceeds from the sale of such personal goodwill as a long-term capital gain. The government argued that the goodwill was Howard Corporation income for three reasons:

- “[The] goodwill at issue was a corporate asset, because Dr. Howard was a Howard Corporation employee with a covenant not to compete for three years after he no longer held Howard Corporation stock;”

- “Howard corporation earned the income, and correspondingly owned the goodwill;”

- “Attributing goodwill to Dr. Howard does not comport with the economic reality of Dr. Howard’s relationship with Howard Corporation.”

“…when there is no employment contract, then the goodwill may be personal.”

The court held that “when there is no employment contract, then the goodwill may be personal.” The fact that Dr. Howard had an employment agreement with Howard Corporation and the covenant not to compete “reinforces the conclusion that Howard Corporation controlled the assets, earned the income from Dr. Howard’s services, and barred Dr. Howard from competing with Howard Corporation.” In this case, even if the goodwill belonged to Dr. Howard personally, it would not have much value, if any, because of the non-competition agreement. That agreement barred Dr. Howard from practicing for at least three years from the date of dissolution for a 50-mile radius, which would “likely discourage patients from following Dr. Howard to a new location… Therefore, the Court finds that the goodwill is a corporate asset.”

Howard – Key Points

Howard reinforces what we have learned in Martin Ice Cream that “when there is no employment contract, then the goodwill may be personal.”

3. Identifying and Transferring Personal Goodwill

An overview of indicators of personal goodwill vs. business goodwill

In Martin Ice Cream, it was established that personal goodwill might exist unless the shareholders “enter into a covenant not to compete with the corporation or other agreement whereby their personal relationships with clients become property of the corporation.” Therefore, the first step in identifying corporate goodwill is to determine whether or not the selling shareholder owns goodwill personally or has transferred ownership to the company by asking the question: “Does the present owner have a non-competition or employment agreement with the seller (the corporation)?” If so, he or she may have transferred ownership in customer relationships, reputation, and know-how to the corporation and therefore not own any personal goodwill to convey in a sale.[13]

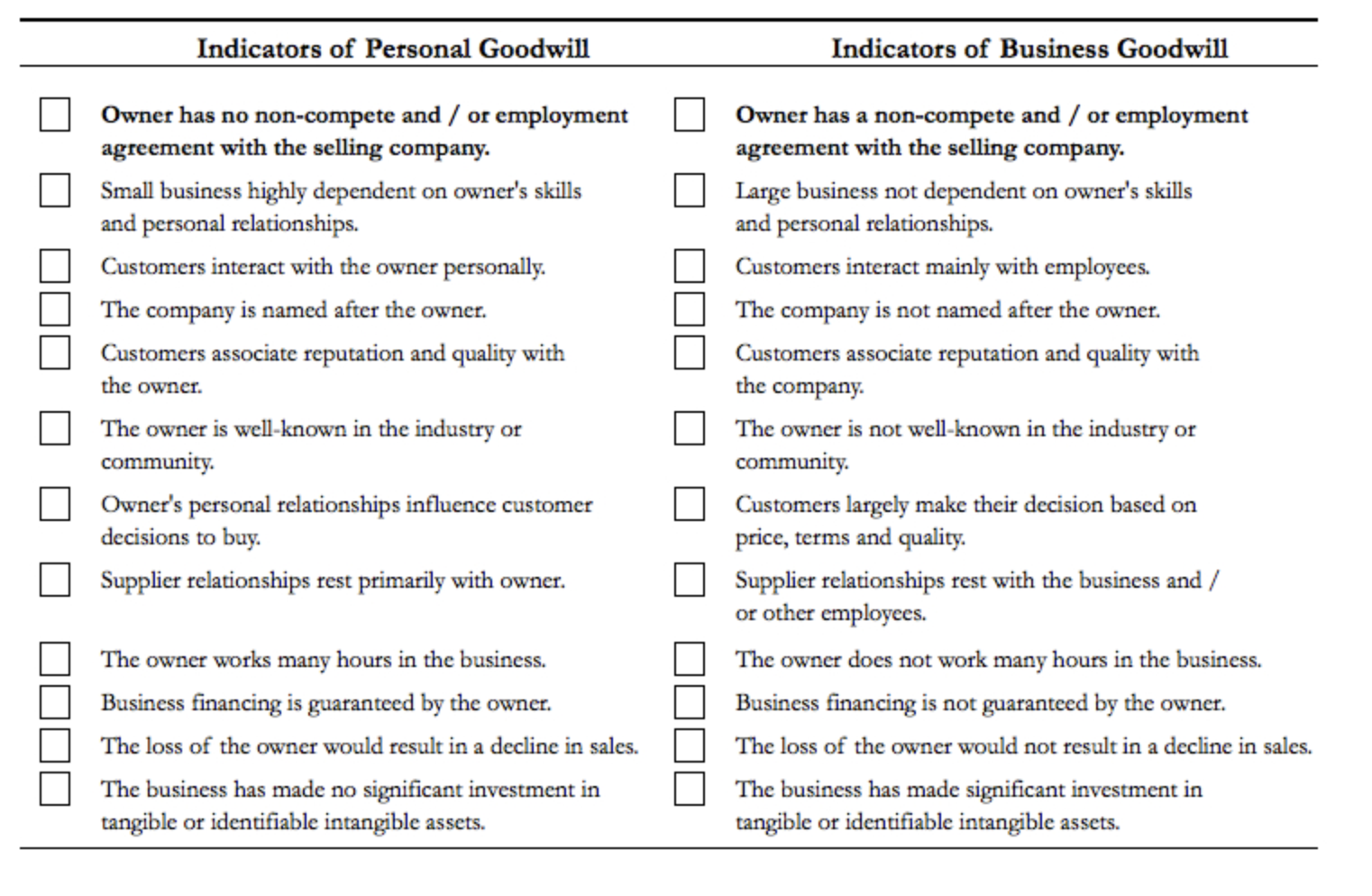

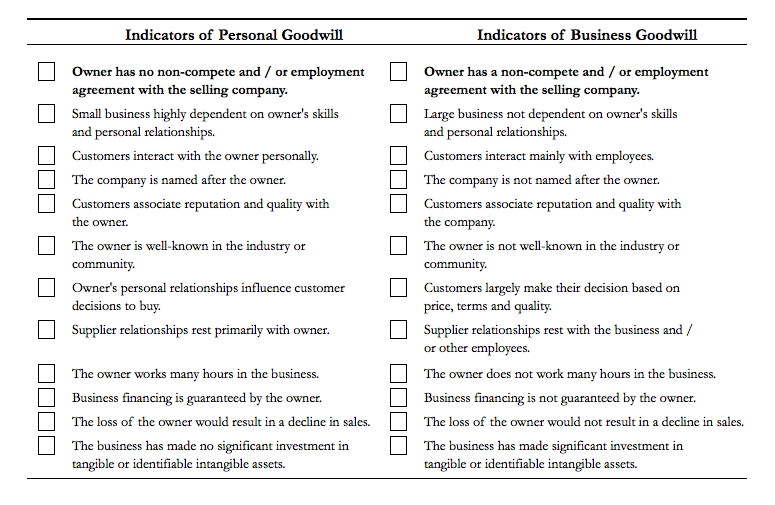

Just because an employment agreement or non-compete does not exist, does not necessarily mean that personal goodwill exists. There are some basic indicators of personal goodwill that a buyer and seller can use to determine whether or not personal goodwill is likely to exist. Although not comprehensive, Figure 3.1 below is a checklist that a party to the transaction can use to determine whether or not personal goodwill exits. A preponderance of checks on the left side of the table indicate the existence of personal goodwill, while a preponderance of checks on the right side indicate that there might be very little, if any, goodwill owned by the selling shareholder personally. Please note, each indicator listed in the figure below is not necessarily weighted equally in the determination of the existence of personal goodwill and the reader should always seek professional guidance from a tax or appraisal expert.

Based on the checklist above, if a seller believes that personal goodwill exists, it must be introduced into the M&A process as soon as possible. As we have learned through careful analysis of case law, the courts have little patience for last-minute, specious allocations to personal goodwill that were not bargained for by the parties. It is not enough to simply claim the existence of personal goodwill in an asset purchase agreement, or a final allocation of purchase price. There are two steps to effectively transferring personal goodwill:

Exclusive Use – Neutralizing Personal Goodwill for the Buyer’s Protection

- The first step in transferring personal goodwill is to limit the seller’s use of that goodwill post-sale. If the buyer does not bargain for a covenant not to compete from the selling shareholder as part of the deal, then personal goodwill has not been conveyed. In fact, the absence of a covenant not to compete as part of the purchase agreement clearly demonstrates (to the taxman and the courts) that any goodwill being conveyed is clearly owned by the business (the corporation) and not the selling shareholder.

- Transfer Goodwill through Consulting and Employment Agreements

The second step in transferring personal goodwill from seller to buyer is to ensure that the buyer can use the personal goodwill that it has acquired, through a transfer of knowledge and relationships from selling shareholder to acquirer. A covenant not to compete is absolutely necessary, but not necessarily sufficient, to convey personal goodwill from seller to buyer.[14] Although a covenant not to compete ensures that the buyer, not the selling shareholder, is entitled to exclusive use of the acquired personal goodwill, it does not mean that the buyer has acquired the proper mechanism to use that goodwill. As you will recall from Solomon, the court reasoned: “[because the acquirer] required non-competitions agreements, but not employment or consulting agreements, of [the sellers] makes it unlikely that [the acquirer] was purchasing the personal goodwill of [the sellers].”

…we can break personal goodwill into two broad classification: 1) contacts and relationships, and 2) expertise, skills, and knowledge.

In the pest control industry, we can break personal goodwill into two broad classifications: 1) contacts and relationships, and 2) expertise, skills, and knowledge. It’s important for the seller to determine exactly what type of personal goodwill is being transferred to the buyer because the effective transfer depends entirely upon the makeup of the personal goodwill. If contacts and relationships with suppliers and customers are being sold, the selling shareholder must be contractually obligated to provide introductions and work with the buyer to facilitate the transfer of contacts and relationships. On the other hand, if the shareholder’s knowledge, expertise or skills constitute all or a portion of the personal goodwill being sold, the acquisition documents must obligate the shareholder to educate the buyer in some way in order to transfer these skills. Although performing pest control services does not take the same level of education and skill as that of a neurosurgeon, there clearly exists skills and knowledge that can be passed on from experienced selling shareholders to an acquirer. This is a concept that is clearly recognized by some of the largest pest control companies in the world. For example, according to a senior executive of acquisitions at an international pest control firm who we interviewed for this article: “We are not just buying pest control accounts when we make an acquisition, we absolutely look to retain employees and high quality management as this is key to retaining knowledge, skills and important relationships. Further, we learn from the companies that join our family, taking best practices from innovative sellers and their management teams.”[15]

Whether contacts and relationships, or knowledge and skills, the seller must convey this goodwill to the buyer and see to it that the buyer has exclusive use of this goodwill. As one commentator suggests:

The shareholder should be under contract for a sufficient period of time to effect a meaningful transfer of goodwill to buyer. Buyers may further entice the shareholder to fulfill these obligations by conditioning payment of a portion of the purchase price on the future earnings of the business (commonly referred to as an “earn-out” [or “hold-back”]).[16]

For example, if Mr. Brown is selling personal goodwill to Terminix as part of the sale of his pest control company, he must specifically identify the makeup of that personal goodwill. Is he selling contacts and relationships? If he doesn’t work for the business post-close, or enter into some sort of consulting agreement with Terminix, how will he convey his ownership in these contacts and relationships to Terminix? Won’t he need to properly introduce the buyer to his contacts? If it turns out that this can be sufficiently accomplished by the employees, then he might not be selling personal goodwill; rather the Company is selling business goodwill. Likewise, if the selling shareholder’s expertise, knowledge, or skills constitute all or a portion of the personal goodwill, then the acquisition documents must obligate the shareholder to educate the buyer or teach its staff these skills, which is generally accomplished through a consulting or employment agreement for an appropriate period of time.

Identifying and quantifying personal goodwill is not enough, the parties to the transaction must assure that there is a proper mechanism put in place to: 1) transfer the personal goodwill from seller to buyer, and 2) ensure that the buyer has exclusive right to utilize the goodwill post-closing. In the following and final section, we will discuss important deal considerations to keep in mind for the effective transfer of personal goodwill.

4. Deal Considerations

Important deal considerations to protect and preserve the transfer of personal goodwill

One of the first steps in documenting an M&A transaction is to determine the proper parties to the agreement. If the transaction is structured as a stock sale, the selling shareholder is the selling party. However, if the transaction is structured as an asset sale, as almost all pest control transactions are, then the selling party may be solely the corporation, or it may be both the corporation and the shareholder (in the case of bifurcated goodwill). If the shareholder personally owns any of the assets used by the corporation, whether tangible or intangible, then both parties should be named in the documentation as soon as possible.[17]

As we discussed in Section One, buyers prefer to acquire assets irrespective of the corporate structure of the seller (whether a C corporation or S corporation). Buyers can choose to acquire assets from the corporation as well as personal goodwill from the shareholder. Additionally, buyers can also acquire the stock of a corporation from the selling shareholder as well as his personal goodwill.

At the onset of the sell-side process, if the seller and his or her advisors have determined that personal goodwill exists, it is prudent to discuss the existence of goodwill with potential acquirers prior to the negotiation of term sheets or letters of intent. Clearly, a very important aspect of the due diligence that the buyer will conduct on the target prior to the consummation of the transaction is to determine exactly who owns the assets that the buyer intends to purchase, such as: the corporation, its subsidiaries or affiliates, or its shareholder(s).

In a pest control acquisition, there are some recurring themes that present themselves in transaction structures that can further bolster and support the argument for the existence and conveyance of personal goodwill. These are:

- Covenant Not to Compete (CNTC) – As we discussed in the previous section, the absence of a CNTC with the selling shareholder and the acquirer will undoubtedly cast the existence and conveyance of personal goodwill in doubt.

- Employment / Consulting Agreement – Is the buyer acquiring contacts? Skills? Knowledge? Experience? If the buyer has no interest in the selling shareholder participating in the business for a period of time post-closing, again, this casts doubt on the existence of personal goodwill.[18] Similar to the CNTC, the absence of a post-closing employment or consulting arrangement with the selling shareholder makes it very difficult to defend the sale of personal goodwill.

- Seller Financing – The majority of pest control acquisitions include some type of seller financing. If the selling shareholder is selling all or a portion of the goodwill personally, then all or a portion of seller financing should be arranged personally by the selling shareholder (as opposed to exclusively by the selling corporate entity). That is to say, the selling shareholder should be named the payee on the promissory note, as opposed to the selling corporate entity, at least for the portion of the personal goodwill that is financed.

- Earnout / Holdback[19] – Most sellers wince at the thought of an earn-out or holdback; however, nothing says the selling shareholder is important to future performance like making a portion of the purchase price contingent upon the seller’s involvement in the business post-close. Holdbacks and earn-outs can be used by acquirers to entice sellers into performing under the terms of their CNTC and employment agreements. If there is personal goodwill involved in the transaction, the holdback / earn-out payouts should be paid directly to the shareholder selling personal goodwill, as opposed to the corporate entity.

- The LOI – Though it goes by many names, the letter of intent, term sheet, indication of interest, etc. should bifurcate personal and corporate goodwill. The parties to the transaction should discuss the existence of personal goodwill prior to the issuance of any offers.[20] It is not necessary that the value of the personal goodwill be quantified accurately at this stage, as long as it is discussed and put in writing.[21]

- The Purchase Agreement – Similar to the LOI, the purchase agreement must name both the corporation and the selling shareholder(s) as parties to the transaction. As we learned in the Solomon and Muskat cases, if the selling shareholder is not party to the purchase agreement, the selling shareholder is not selling goodwill, the corporation is. Game over.

- Form 8594 – Buyer and seller must report the final allocation of purchase price to the Internal Revenue Service on Form 8594. It’s very important, especially in a personal goodwill situation, that the initial allocation of purchase price is negotiated at the LOIstage and a draft Form 8594 is agreed on by both parties wherein goodwill is properly bifurcated on this form.

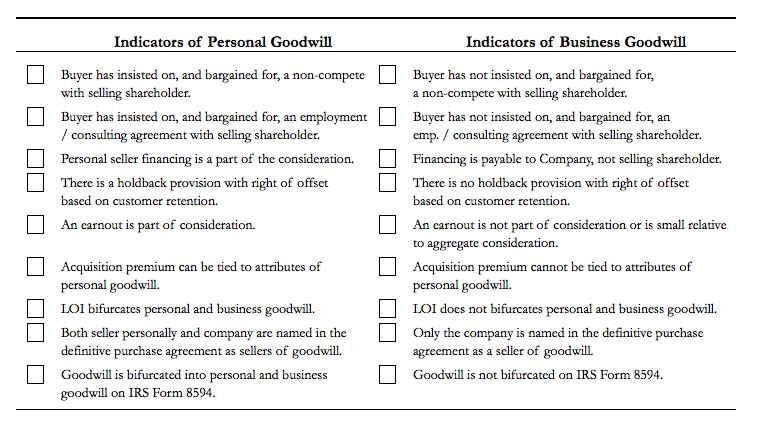

The figure below is a brief checklist of deal structure-related indicators of personal versus corporate goodwill. The prudent buyer and seller should review and utilize the checklist below throughout the deal process.

A Word on the Valuation of Personal Goodwill

Although we have spent significant time discussing the identification and conveyance of personal goodwill, we have been silent on the valuation of personal goodwill. Valuation for tax purposes is a highly technical topic and best left to your M&A advisor and business valuation expert as the consequences of getting it wrong can be disastrous for the seller. If either a buyer or seller asserts the existence of personal goodwill as a saleable asset, it is imperative that the parties obtain an appraisal of its value from a qualified business appraiser with experience in the pest control industry. The appraisal is an important part of the due diligence process and will dictate the portion of the purchase price that will be allocated to personal goodwill. In our experience, we have seen allocations of personal goodwill ranging from 10% to 90% of the aggregate transaction value.

Conclusion

The majority of the sellers in the pest control industry utilize lawyers and accountants that are unaware of the tax-saving benefits of selling personal goodwill as an asset class, and who consequently do not use the concept of personal goodwill to their clients’ advantage. When advisors are unaware of the substantial benefits of utilizing personal goodwill in the context of a corporate sale, sellers can find themselves at best in very difficult tax situations, and at worst with a dead deal. Furthermore, if buyers do not protect themselves throughout the documentation process, they can end up receiving substantially less than they bargained (i.e., purchasing personal goodwill but not having exclusive use).

Large acquirers are beginning to understand the benefits to the selling shareholders and have begun educating their acquisition teams to the importance of being flexible with regard to structuring the purchase of goodwill – both personal and corporate. In a recent conversation with Kevin Burns, VP of Acquisitions at Arrow Exterminators, he said, “If buying personal goodwill is going to help a seller, we will work with him any way that we can. As a private, family-owned business, we are flexible and able to think outside the box when it comes to deal structure. In fact, some of our largest acquisitions have involved the purchase of personal goodwill from sellers that own C corporations.”

In recent years we have used the bifurcation of goodwill to our clients’ advantage both on the sell-side as well as the buy-side. For our sell-side clients, it has helped mitigate their tax bills by millions of dollars and for our buy-side clients we have been able structure lower purchase prices by being creative with goodwill. If you are selling a C corporation, or contemplating acquiring one, personal goodwill might hold the key to a better deal for both parties.

[1] While this article focuses on the sale of assets by a C corporation, the techniques discussed are also applicable to S corporations that are subject to built-in gains taxes arising from a conversion from a C corporation to an S corporation within the 10-year conversion window.

[2] A flow-through entity, such as an LLC, Subchapter S Corporation, partnership, etc., does not pay entity-level taxes, but rather the income flows through to the ownership, where it is taxed on an individual basis.

[3] Excel Environmental and Mr. Brown are fictional names, any similarities to real persons or entities are purely coincidental.

[4] Corporate income tax rates vary by state, so seek specific advice from your tax advisor. Unlike individuals, corporations do not receive preferential tax treatment for capital gains versus ordinary income.

[5] Assumes the federal long-term capital gains rate of 15% plus state capital gains tax of 5%, which varies by state.

[6] In this example, the tangible assets are acquired at the Company’s tax basis in those assets. The goodwill generated in the acquisition results in the $10 million differential between the purchase price and the Company’s tax basis and goodwill is amortized for 15 years for federal tax purposes.

[7] IRS Publication 535: Business Expenses, Ch. 9, Cat. No. 15065Z

[8] Justice Story penned a common legal definition of goodwill often cited by the courts: “The advantage or benefit, which is acquired by an establishment, beyond mere value of the capital, stock, funds, or property employed therein, in consequence of the general public patronage and encouragement, which it receives from constant or habitual customers, on account of its local position, or common celebrity, or reputation for skill or affluence, or punctuality, of from other accidental circumstances, or necessities, or even from ancient partialities or prejudices.” See Carmen Valle Patel, Note, Treating Professional Goodwill as Marital Property in Equitable Distribution States, 58 N.Y.U.L. Rev. 554, 561 n.44 (1983).

[9] Goodwill and going concern are distinct concepts, however, for the purpose of this article we will focus solely on goodwill.

[10] Alicia Brokars Kelly, Sharing a Piece of the Future Post-Divorce: Toward a More Equitable Distribution of Professional Goodwill, 51 Rutgers Law Review 564 (1999).

[11] There was no double taxation, but Robert and Richard Solomon did not receive long-term capital gains tax treatment.

[12] In Muskat, the court provided the following discourse on the “strong proof” rule: “The strong proof rule is peculiar to tax cases. It applies when the parties to a transaction have executed a written instrument allocating sums of money for particular items, and one party thereafter seeks to alter the written allocation for tax purposes on the basis that the sums were, in reality, intend compensation for some other item. The rule provides that, in order to effect such an alteration, the proponent must adduce “strong proof” that, at the time of execution of the instrument, the contracting parties actually intended the payments to compensate for something different…. The heightened standard strikes the appropriate balance between predictability in taxation and the desirability of respecting the contracting parties’ real intentions”

[13] In Norwalk, however, the Court recognized the existence personal goodwill even though an employment / non-competition agreement had previously existed but had terminated prior to the sale (or in that case, liquidation of the corporate entity).

[14] Masquelette’s Estate v. Commissioner, 239 F.2d at 326 (“We think it clear that the agreement not to compete here was one of the means used by petitioners to assure the purchases that the entire goodwill of petitioners . . . would be effectively conveyed to their successors…”)

[15] Due to the fact that the interviewee works for a public company, he requested to remain anonymous.

[16] Darian M. Ibrahim, “The Unique Benefits of Treating Personal Goodwill as Property in Corporate Acquisitions,” Delaware Journal of Corporate Law, Volume 30, p.32.

[17] If shareholders are selling personal goodwill, they should be included in the “paper trail” of the deal as soon as possible, ideally at the term sheet or LOI stage.

[18] See the discussion on the Solomon case in Section Two.

[19] A holdback is a common contingent-pay mechanism found in pest control acquisition structures whereby the acquirer holds back a portion of the portion price contingent upon some future performance metric. Generally, acquirers will hold back 10% to 20% of the purchase price based upon customer retention at some future date (i.e., six to twelve months from the closing). An earnout, similar to a holdback, is generally used to bridge the gap between buyer and seller expectations of future performance. Because the extreme majority of pest control acquisitions are priced by strategic acquirers utilizing historical performance, fast-growing pest control acquisition targets can be penalized if they are growing at a rate substantially faster than that of the industry average.

[20] The buyer will not initiate the personal goodwill discussion unless: 1) the seller is demanding a stock purchase; 2) the buyer understands how bifurcating goodwill can help the seller. Therefore, the onus is on the sell-side advisor to begin these conversations while giving the buyer guidance on deal terms and structure.

[21] Clearly the LOI is executed prior to the buyer commencing diligence. At this stage of the process, it is very difficult for both buyer and seller to bargain and substantiate an appropriate value for both personal and corporate goodwill – this will be discovered and negotiated. However, it is appropriate at this stage for the parties to begin the paper trail that will ultimately support the existence of personal goodwill.